A Healthy Comfort Level with Ambiguity is an Asset

A note to my team on leaning into not knowing, and channeling our inner Dora the Explorer

!! Red pill, Blue pill warning !!

If you are not a fundraiser, the text below will give you some insight into “how the sausage is made.” This may be a turnoff for you. Everything we do as fundraisers is in the interest of the donor and the organization, and we don’t do anything that forces someone to give. We aim to elevate the donor, their agency, and connect them with opportunities to materialize their vision of the world. However, fundraising at scale requires management. How we talk about this can give the impression that donors are reduced to a number, their capacity to give, merely prospected line of ore to be mined, and all kinds of other not-so-kind descriptions. We don’t treat donors this way, nor think of them this way, but if this impression would materially affect how you feel about our work, about fundraising, or worse, about giving, maybe this one is not for you.

Onward:

The big ask this week was to go through our portfolios and identify those donors who may be prospects for the Issue Based Campaign. This exercise is one that typically stretches any fundraiser’s level of comfort with ambiguity. With time, you will get to know your donors better, and this becomes easier because you will be in a position to make better informed guesses. For now, just make a good faith guesstimate of whether the donor could be interested in Center for Working Families (CWF), what amount they could give to the campaign, and how likely you think it is that they will respond positively.

That you don’t know for sure is OK for four reasons.

Reason 1: The gift range chart already accounts for most people to say “no” to a proposal

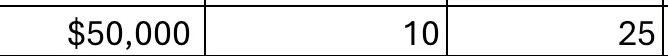

Look at the $50K line above. In this scenario, 10 out of 25 potential donors say yes to a proposal to support the campaign with $50,000. However, we are also EXPECTING 15 people to say no to a proposal. So, organizationally, we have already accounted for possibility of a no, so we are comfortable with the ambiguity of not knowing the answer at this point.

And that’s alright.

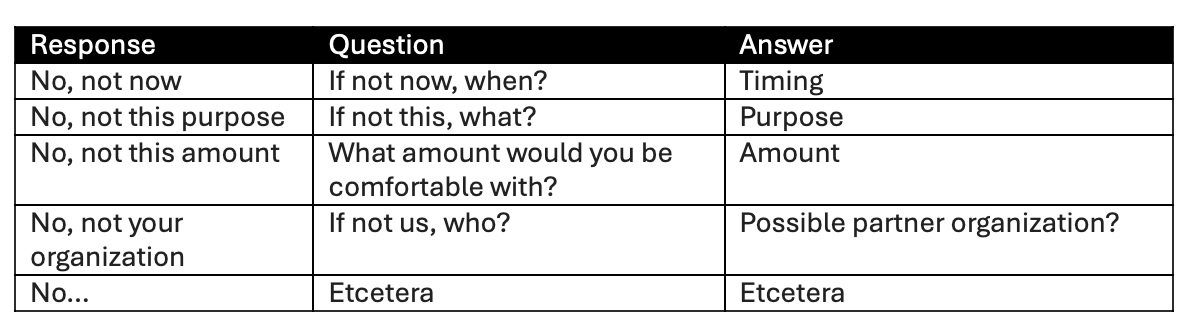

The alternative responses to an emphatic yes are:

A conversation rarely stops at a “no,” and despite it not being fun to hear it or be proven wrong about your prediction of their interest, it gives you the opportunity to explore other interest areas with the donor. You are already in the room, so they have invited you in, and given you their permission to ask. This is a chance to really home in on what it is that makes this particular person tick.

But this is applicable only if you’re already having the conversation.

Reason 2: It commits you to planning to ask

If you don’t plan on asking anyone, you can already give up on your campaign. You know that what you’re raising money for fits within the mission of your organization. You know that this will do good in the world. You know that people have supported your organization’s mission in the past and are seeking similar good in the world. This would suggest there are people out there who would support this effort.

Planning who to ask from that “community of the committed” (thanks Jim Hodge 😃) is committing yourself to a roadmap. Even though you are uncertain of some of the roads you’re taking, you know that there are a number of miles/kilometers between you and the destination. Even though you don’t know the outcome of all the asks you’re planning, you know you have to plan at least a certain number and be comfortable ending up with some alternative outcomes (see the “no, not …” table above).

For our CWF campaign alternative outcomes can be: focusing on a specific effort, like financial literacy coaching, or focusing on a specific county, or to go to a different gift level. Any of those outcomes are valid and would NEVER be achieved if you didn’t add the donor’s name to the list of people to talk to about this effort, even though your prediction may have been off.

Reason 3: This exercise requires you to take the donor’s perspective

Thinking through whether this person is a potential donor to your project, requires you to take their perspective, review what they have given to before, at what levels, for what reasons, with what consequences, etc. This gets easier the better you know someone and will allow you to make more accurate predictions. Not knowing is ok, because when you review all the evidence and make an informed prediction, you do those kinds of things that make you ready to get to know the donor and have meaningful conversations when you do meet them and explore their interests (my advice is, again, don’t be creepy – knowing their cat’s name before you ever meet is… uhm… awkward).

Reason 4: If you don’t know them well enough, this is a prime opportunity to explore with the donor

This is where being comfortable with ambiguity comes in really handy, because it incentivizes you to go out and explore with the only person who can definitively tell you whether or not they’re interested in learning more: the donor themselves. So lean into the feelings of not knowing and use that energy to go find out. Schedule that call, coffee, and talk to them.

Having a genuine interest in the donor’s opinions, values, interests, and passions is almost always well-received. Since at worst the thing you will hear is “no, {fill in the blank},” you have an opening to find out those things that DO matter to them. All this to say, is, lean into ambiguity, make cautious, but optimistic predictions, and go out and explore with the donor.